No Justice, No Us

April: Earth Month. Ever a season of change, birth, renewal. It is a time when we notice the smell of fresh, warming earth, the feel of sunshine on our cheeks, the sound of migrating birds cheering their return. Here at Lower Phalen Creek Project, April is a time to give thanks to our Uŋčí Maka — our Grandmother Earth — and a time to express gratitude for all the plant and animal relatives who come back to us and enrich our lives.

Yet in this season, as we see the snow melting away and the soil laid bare — as our world feels ripe with possibility and an impending burst of life — we also find certain inconvenient truths rising to the surface. Many of us, no matter where we live, can clearly see how climate change is impacting our lives. For many BIPOC communities, though — and right here on the East Side, in fact — a polluted, unsafe environment is nothing new. Industrialization across Turtle Island has brought wealth to some, and sickness to many. This shameful practice is a cornerstone of American society, and it has a name: environmental racism. What does this mean, you ask? We like this definition, from Green Action, which names environmental racism as “the institutional rules, regulations, policies or government and/or corporate decisions that deliberately target certain communities for locally undesirable land uses [...] resulting in communities being disproportionately exposed to toxic and hazardous waste based upon race.” Put more simply, it means that when powerful institutions know the harmful effects of industry and development, they almost always choose to extend that harm from our planet to our people.

Pictured is a map of Saint Paul’s East Side, with a yellow circle displaying a one-mile radius from Wakáŋ Tipi / Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary. Over 30 sites within the radius currently report toxic releases, water discharges, air pollution, or Brownfields to the Environmental Protection Agency. The map is part of the EPA’s EJSCREEN Mapping Tool.

But what does environmental racism look like? First and foremost, it is about land. It is about the genocide and displacement of Indigenous nations across Turtle Island. It is about the decimation of the bison and the prairie to make room for cattle and for corn. It is about the United States government dishonoring ill-begotten treaties and starving Dakota people on our own homelands, and following this atrocity with war and exile.

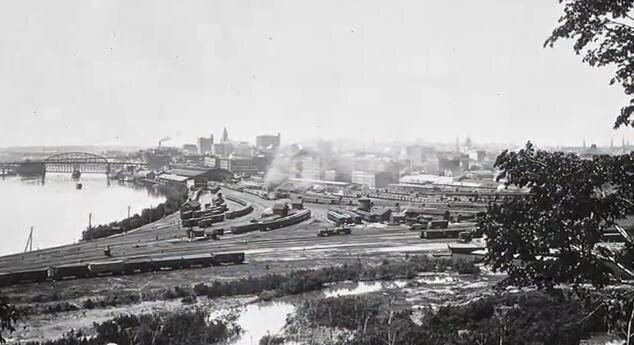

Environmental racism continued after the War of 1862 with the development of the City of Saint Paul. The East Side itself is a prime example of this process. First came an altered landscape. The riverbed of the Mississippi was dredged and dumped on the shoreline to create more space for an active port. Railroad companies, seeking a way to transport resources from further inland, blasted Wakáŋ Tipi cave with dynamite to force a pathway up between the sandstone bluffs of the East Side and the hillier parts of downtown Saint Paul. With the expansion of industry across the state of Minnesota, Saint Paul’s population quadrupled — from 33,000 in 1880 to 144,000 in 1890. This boom was good for businesses, but caused the unequal pattern of development, displacement, and neglect that characterizes Saint Paul communities today. In the twentieth century, the practice of redlining designated East Side neighborhoods, inhabited largely by people of color and recent immigrants, as “definitely declining” or even “hazardous” areas. During this time, East Side businesses like 3M, Whirlpool, and Hamm’s Brewery brought thousands of jobs to the area, but ultimately produced significant amounts of industrial pollution and relocated their operations, restarting the cycle of disinvestment and decline.

Today, the East Side faces many of the same issues it faced over one hundred years ago. Lower health outcomes among East Side residents are augmented by close proximity to highways, a legacy of heavy industry, and limited access to transit, healthcare, and healthy foods. As Zedé Harut of Grand Risings Farm explains it, the resulting situation is not accidental. What we know as “food deserts” are not naturally-occurring nutritional dead zones, but rather the product of processes like redlining and disinvestment. Similarly, the way to resolve these issues is not simply to drop “healthy foods” into these neighborhoods. Much like the process of restoring and remediating polluted land, food deserts require comprehensive changes in policy and social practices so that the residents in these neighborhoods can grow and thrive.

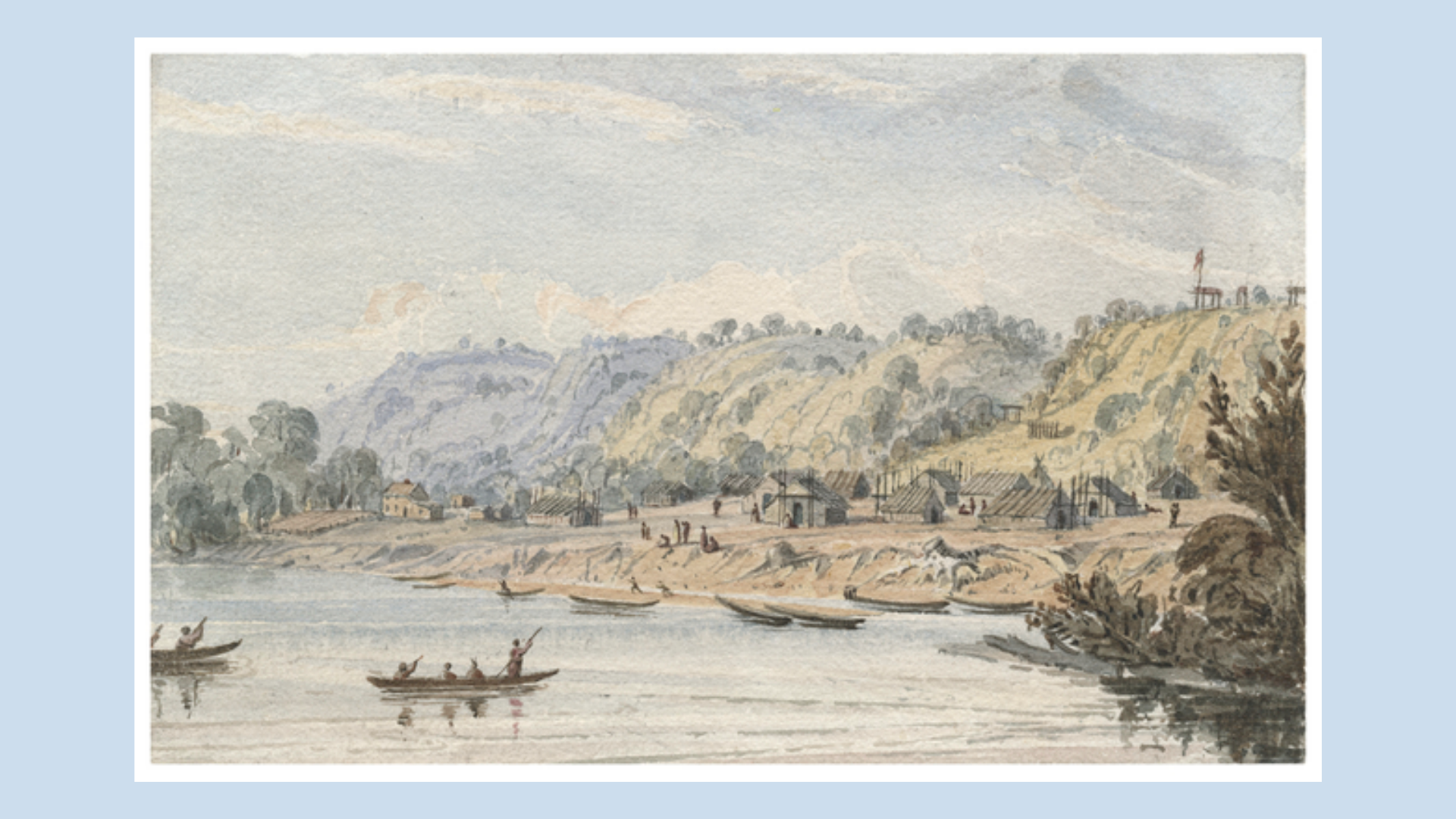

But let us hone in, for a moment, on how one small area can embody the systems we’re discussing. The images above show how the area of Wakáŋ Tipi has been thoroughly shaped by environmental racism — but these images also show it has been reshaped — and reclaimed — through practices of environmental justice.

As the story of Wakáŋ Tipi shows us, environmental racism is not solely a result of industrial production; it is as much a process of neglect as anything else. As much destruction and damage as the railroad caused to this site, years of abandonment allowed over 50 tons of trash and litter to accumulate in this 30-acre parcel of land. Relatedly, the industrial activities on site contaminated the soil with mercury and asbestos. The capitalist practice of using, abusing, and discarding land creates a vicious cycle of waste. But it does not need to be this way. The images above remind us that human beings have lived on this land — cared for it and been cared for by it — for generations. Just as human beings need this land, this land needs human beings.

There are others who recognize that the justice we seek is one that heals us at the same time that it heals the land. We seek the type of justice that Mexica artist, musician, and activist Xiuhtezcatl Martinez writes about when he describes a shift in our collective conscience. We seek the type of justice first set forth in 17 Principles of Environmental Justice at the First National People of Color Environmental Justice Leadership Summit in October of 1991: namely, an environmental justice that “affirms the sacredness of Mother Earth, ecological unity and the interdependence of all species, and the right to be free from ecological destruction.”

What do these values look like to us? How do we apply them in our lives? If we start with the sacredness of Uŋči Maka, all else follows. This all-encompassing respect for our earth is the basis for Dakota lifeways and so much of traditional ecological knowledge. We see ecological unity reflected in the Dakota value of mitákuye oyásiŋ — we are all related. If we are to view every element of our entire ecosystem not only as living, but as a relative, we recognize our interdependence, and take full responsibility for our mutual thriving. The practice of the honorable harvest bears out this shared responsibility. As Potowatomi scientist and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer describes it: “the Honorable Harvest, a practice both ancient and urgent, applies to every exchange between people and the Earth. Its protocol is not written down, but if it were, it would look something like this:

“Ask permission of the ones whose lives you seek. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last.

Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

Take only what you need and leave some for others.

Use everything that you take.

Take only that which is given to you.

Share it, as the Earth has shared with you.

Be grateful.

Reciprocate the gift.

Sustain the ones who sustain you, and the Earth will last forever.”

As Kimmerer is careful to emphasize, the honorable harvest is not a hard and fast rule but rather a practice, a way of being in and with the world. This month, as we prepare 500 medicine bundles for our Indigenous community members, our minds are occupied with the nature of harvest. When encountering our traditional medicines in their natural habitats, we encourage all of you to consider the honor of your harvest.

Another way in which we see the interdependence of all species is in the conversation surrounding so-called “invasive” plant species. Conventional Western knowledge sees plants as either beneficial to surrounding biodiversity and belonging in a habitat, or detrimental and deserving of removal. And make no mistake — some plant relatives take up more space for themselves, crowding out other species and degrading the quality of the soil they live in. While our habitat restoration projects demand that we remove these misplaced relatives so others can thrive, we seek to do this work in a manner that reflects the agency and life of the so-called “invasives.” For instance, we can find multiple uses — medicinal, edible, functional — for many of these relatives. If we work toward this relational change, we may find it easier to view our ecosystem as a living, breathing, interrelated whole, and in so doing, remember how we used to exist with the land and water and all other beings on this earth: with justice.

This Earth Month, we call on all of our supporters to join us in taking action toward environmental justice. Here are a number of options and opportunities for people to protect and nurture the lands and waterways in the Twin Cities. You can choose one or all or look for other opportunities to get involved in your community.

Volunteer — If you want to be boots on the ground, join us for the CityWide Spring Cleanup on April 24th at Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary or attend one of our Restore Events.

Learn — Deepen your connection with the local environment and view our recently recorded All About Pollinators! Webinar or Sacred Dakota Lands and Waters, both on our YouTube page.

Donate — Help power the work of Lower Phalen Creek Project all throughout the year by donating to our Spring Fundraiser! This year our goal is to raise $7,500 and your support will ensure that our work in Environmental Education, Urban Conservation and Restoration, and Cultural Connections & Healing continues.