We are in the midst of one of the longest spring seasons in recent memory. In the month of March, statewide, the preliminary average temperature was 7.4 degrees above normal. This spring overall has followed a recent and growing trend of warmer and wetter months.

A 2019 fact sheet from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources displays the many ways in which our climate is steadily changing. These changes have many direct impacts on our human and non-human relatives throughout the ecosystem.

We could write a separate post dedicated solely to climate change and its disparate impact on lower-income and POC communities. But here in May, as we are surrounded by fragrant blooms, vibrant colors, and the music of birdsong, it feels important to explore and celebrate all of this life bravely bursting forth into our world. Similarly, while we will face increasingly difficult challenges in the quest to keep our ecosystem intact, we can find solace in the strength, wisdom, and beauty of Indigenous ways of knowing, being with, and caring for our Uŋči Maka. These values have been with us for generations, and they will carry forward for the generations to come.

Native prairie grasses sprout up through detritus in an area near one of Wakáŋ Tipi’s three wetlands. Five acres of prairie were treated by prescribed burn in April. Clumps of milkweed fluff—released late from last fall’s pods—cling to the new-growth grass stems.

One such value—the controlled, intentional burning of a landscape—is becoming increasingly important in a rapidly warming climate. With higher average temperatures and extreme weather events fueling rapid oscillations between periods of heavy precipitation and extended drought, our plant communities are more susceptible to wildfires. The settler-colonial management practice of fire suppression has also augmented these risks, prioritizing commercial timber operations and other infrastructure projects over the basic stewardship of fire-dependent ecosystems. An article detailing the efforts of the Yurok Tribe to restore Indigenous ecological management practices to California’s lands describes the context of this settler-colonial philosophy: “Fire-suppression rules have sharply curtailed the ability of Indigenous communities to conduct traditional burns. Native Americans still face persecution and penalty when they try to use fire in line with their traditions—even on public lands where they often hold treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather.” Prescribed burns allow for massive regrowth and encourage biodiversity; without them Indigenous communities not only lose the vital cultural resources provided by this practice—the cultural practices themselves become lost.

It is with this perspective in mind that we approached a five-acre controlled burn at Wakáŋ Tipi / Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary in mid-April. Though this practice is currently conducted by the City of Saint Paul Natural Resources department, it is valuable to have the land cared for in this way, and with coalitions like the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network connecting more groups with one another, Indigenous communities are beginning to reclaim this relationship to land and to fire.

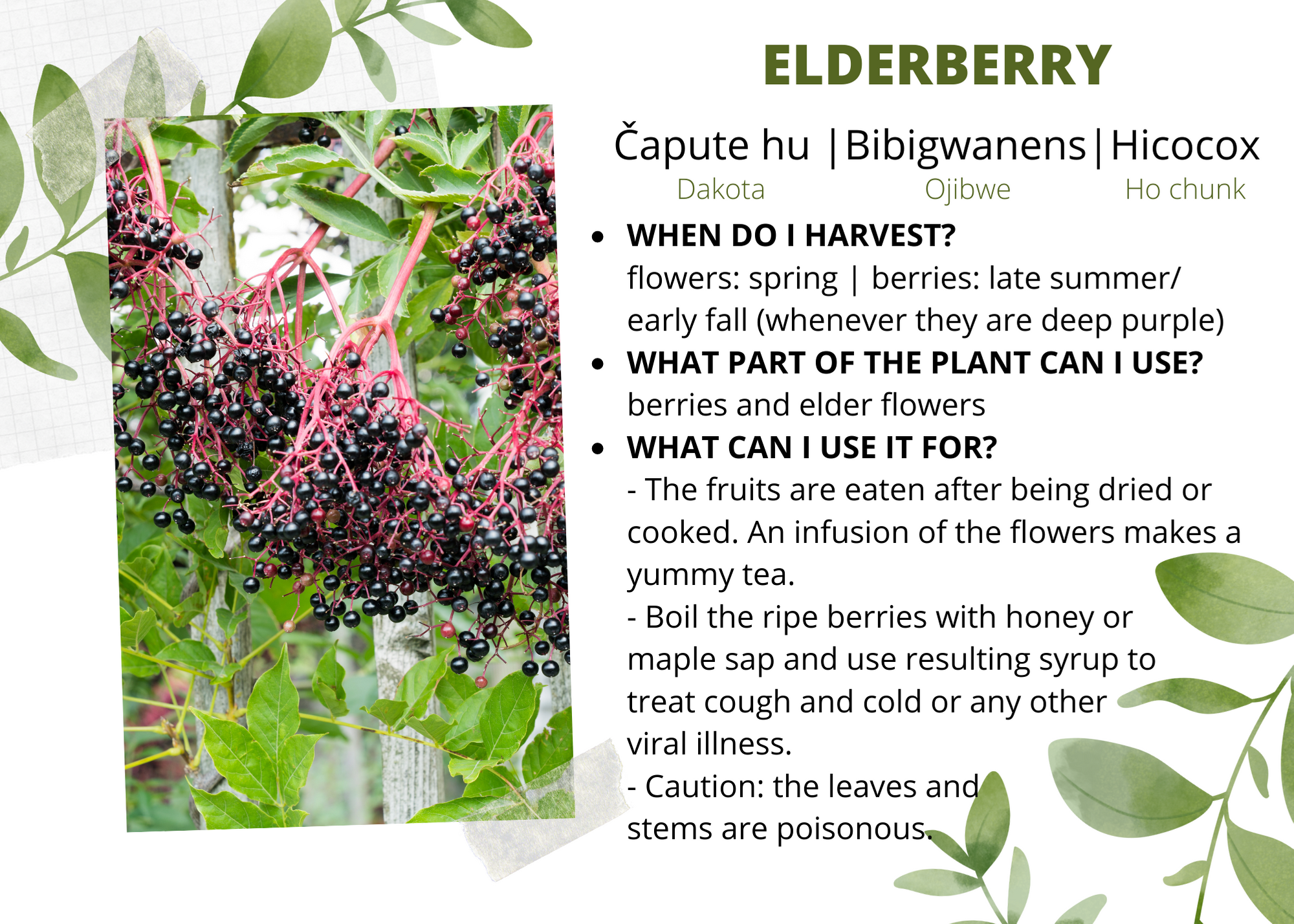

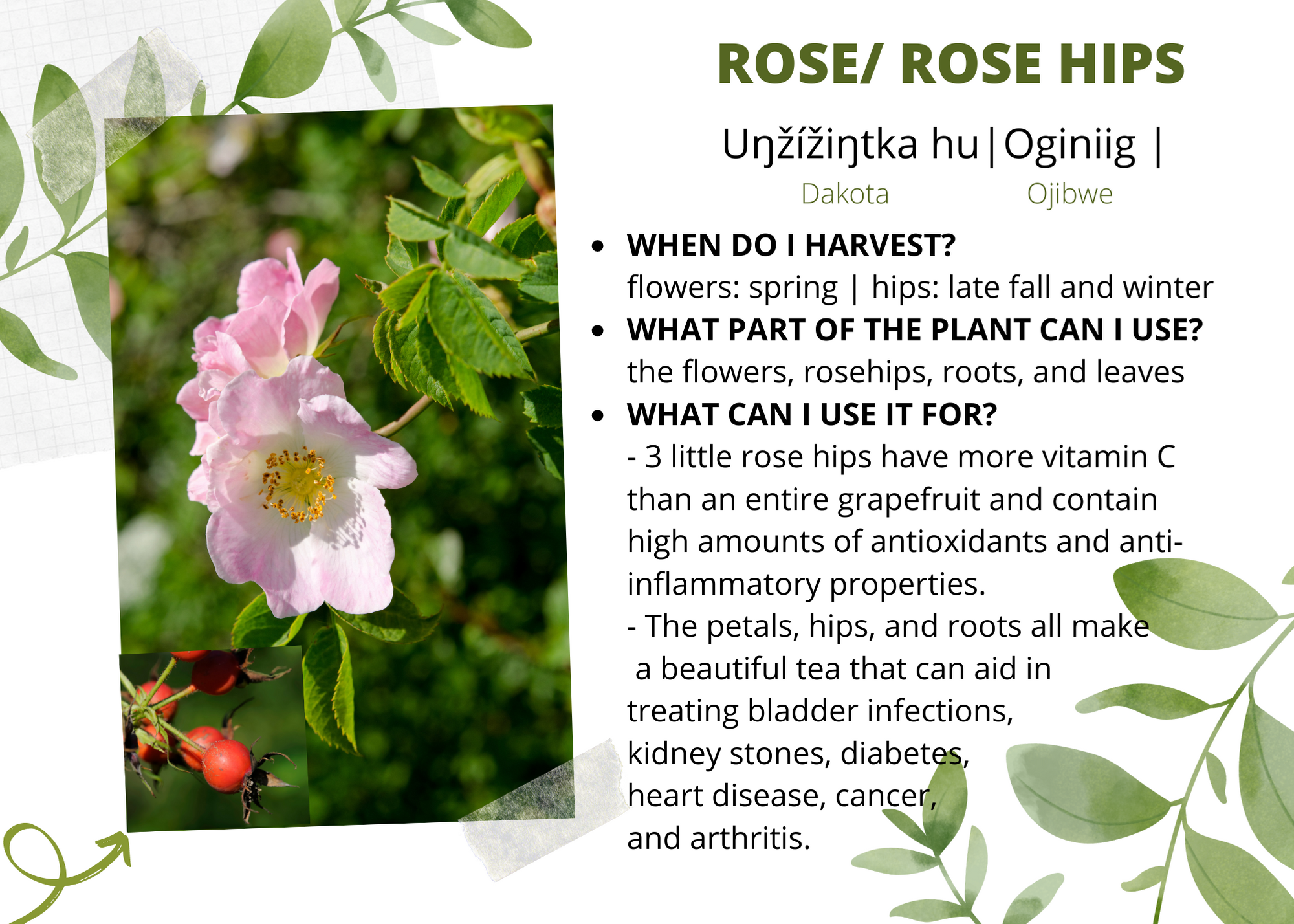

Dakota people have survived and thrived for generations with the passed down knowledge of our traditional foods, plant relatives and medicines. This spring, LPCP’s Communications & Cultural Programs Coordinator, Mishaila Bowman, created this incredible plant medicine guide to continue this legacy of sharing the ways in which our plant relatives care for us.

Join us on Wednesday, May 26th, from 6-8pm, and learn from speakers Tipiziwin Tolman (Wičhíyena Dakota and Húŋkpapȟa Lakȟóta), Ella Robertson (Sisítuŋwaŋ Dakota) and Hope Flanagan (Seneca, Turtle Clan) about the importance of using our traditional plant medicines like cedar, mint, elderberry, bear root, coneflower, rose hips and more through COVID-19 and beyond.

Wičhágnaška (buffalo currant or golden currant) spotted at Wakáŋ Tipi in late April.

Elsewhere at Wakáŋ Tipi, many of our plant relatives are again showing themselves. Buffalo currant, pictured above, is one of many shrubs starting to come into full flower. Both the berries and flowers of this plant are edible! Other fruit-bearing shrubs and trees you may see throughout the sanctuary include elderberry, chokecherry, hackberry, and many more!

As we’ve mentioned in previous blog posts and on our social media, you may also encounter many displaced plant relatives throughout the sanctuary. Displaced plant relatives often discourage the mutual thriving of other species, usually by spreading rapidly, degrading soil quality, and making themselves difficult to remove. Research conducted on-site at Wakáŋ Tipi / Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary has found that many portions of the 27-acre sanctuary have become dominated by displaced plant relatives like burdock, buckthorn, garlic mustard, crown vetch, thistle, and more. Accordingly, in 2021, our first of a five-year Natural Resource Management Plan, our schedule calls for the removal of many displaced plant relatives to encourage healthier soils and increased biodiversity. We accept this practice as necessary for a better ecosystem, but we also find ourselves wanting to respect these displaced relatives, celebrate them for what they provide, and acknowledge the value they hold.

Many of our friends and knowledge keepers have long celebrated and appreciated the value of displaced and discounted plant relatives. The wonderful staff at Dream of Wild Health continued a long legacy of beautiful relationships with our plant relatives during their recent Sacred Medicines & Garden Beginnings workshop. Elsewhere, ethnobotanist and ecologist Linda Black Elk is currently wrapping up a 7-part virtual workshop series focused on Culturally Important Plants and the values, practices, and relationships Indigenous communities have developed with them.

We like to end each blog post with a call to action, in some shape or form. This month, above all else, we encourage you to spend time outside, learning the names of your plant relatives, getting to know them. If you forage or harvest any of these relatives, do so with respect and mindfulness for each plant. Consider the principles of the honorable harvest. Make sure you are not harvesting from a location with high amounts of pollutants and toxicity in the air, water, or soil. And if you remove a displaced plant relative to make room for the thriving of others, remember that this plant, too, has a place and a value in our world. Whatever you do, take a moment to place yourself—and the plant relatives you spend time with—in context with the entirety of our ecosystem.